A fine Morion, attributed to Pompeo della Cesa, Milan, 1585 - 1590

Weight: 1,68 kg.

Height: 29,5 cm.

Width: 23 cm.

Length: 37 cm.

This morion helmet is elegantly forged from one single plate of iron, rising to a back turned stalk at its apex and showing a file-roped down turned edge at

each side, seperated from the brim by a recessed chamfer. Towards the front and back end the brim tapers upward to an acute point. On the back there is a

plume holder made of brass with scrolled edges and punched ornament attached to the helmet by two brass-capped iron rivets. Similar rivets hold ornamental

rosette washers and remainings of the lining inside, eight on the right side, seven on the left (one missing). The helmet’s surface is decorated by etchings,

partly fire guilt, silhouetting against a back ground of stipled areas, blackened where surounding trophies and figural ornament, guilt where contrasting

scroll work ornament of plain borders repeating the black stippled area in the center. There are four large panels depicting classical warriors and trophies,

sourounded by a guilt band including an etched wave ornament. Alternating these panels you can find bands of interlace and oval cartouches, being separated

by vertical blank stripes and two horizontal ones at the base that enclose the row of washers, sourrounded by stylised leaves, contrasting an acanthus

foliage ornament on the brim.[...]

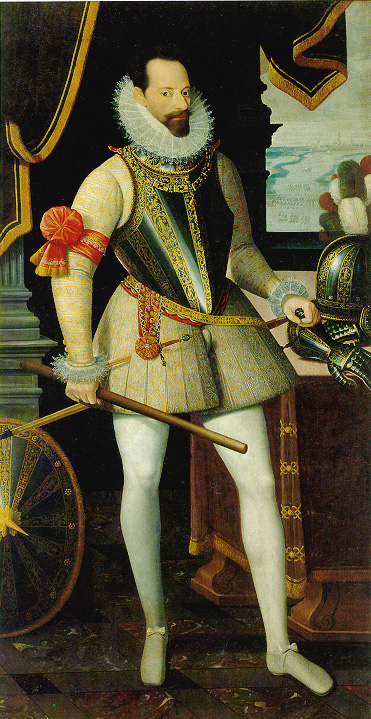

Background

The morion helmet developed from the 15th century war hat, in particular the Spanish type that was called cabacete. As a very popular helmet the morion

came into use all over Europe and was found on the battle fields until the first half of the 17th century. Especially among the infantrymen like those

wearing the pike, the emperors personal guards and town or city defenders it formed an integral part of their half armour. It was common practice that

officers wore the same type of equipment in the field, hower corresponding to their rank it was manufactured in a higher quality level and elaboratly

decorated. Certainly the equipment also served as a status symbol and the more important a military leader was, the larger were his investments in splendid

arms and armour. When the highest ranking emperors of Renaissance Europe commissioned such an amour they often ordered a so called garniture. This meant

that an armour could be adjusted for various types of usage, like different forms of the tournament or for wearing in the field by exchanging components,

all being decorated in the same magnificent design. In the late sixteenth century Milan was the most important centre for the manufacture of these works of

art. Leading armourers who created luxurious etched designs were a master who signed with the initials IFP, for example shown on a half amour in the Art

Instiute Chicago.(1) Another signed with a triple towered castle, examples being a visor and bevor in the same collection.(2)

Particularly renowned however is:[...]

Pompeo della Cesa (Chiesa), 1537 – 1610

It is recorded that Pompeo lived near the Porta Comasina in Milan back in May 1560 being the son of Vincenzo. His municipality was Santa Maria Segreta,

near the area were the armourer’s shops were located. Presumably he worked there for Giovani Pietro da Ferno finally becoming a master craftman himself

about 1570, having his workshop at Castello Sforzesco. Soon the highest ranking emperors of Renaissance Italy belonged to his clients. According to extant

correspondence and invoices some of Pompeos commissions can be reconstructed in detail. Back in 1586 he manufactured an armour for Allesandro Farnese (1545

– 1592), Duke of Parma and in 1592 for Vincenzo I. Gonzaga (1562 – 1612), Duke of Mantua. In the same year Pompeo got an invitation to the court of Philip

II of Spain (1527 – 1598) who was also Duke of Milan.

Other important relationships persisted with Emmanuel Philibert (1528 – 1580), Duke of Savoy, Francesco I de Medici (1541 – 1587), Juan Fernández Pacheco

(1563 – 1615), 5th Duke of Escalona and the Dukes of Infantado. The reputation of Pompeo della Cesa spread all over Europe, even leading to commissions

from uproad: A signed half armour of Henry Herbert, 2nd Earl of Pembroke (1538 – 1601) is still preserved at Wilton House, Great Britain.[...]

Pompeo signed his works occasionally by a mark showing a crown with two crossed keys. Sometimes he also etched a cartouche within the ornaments that bore

the inscription “Pompe” at its edge illustrating a classical warrior in the center with a trumpet in one hand and a kind of flash in the other. The same

inscription was also used on a ribbon held by two putti.

Context of the present morion

Having a closer look at the constitution of the helmet’s ornamental design the bands of guilt and blackened interlace alternating with cartouches showing

classical warriors immediatly attract attention. These bands intervene with panels of trophies on the present helmet. Since this pattern does appear as a

distinctive feature on several signed works like a cap-à-pie armour in the Museo Stibbert, Florence, (3) a half-armour in the Philadelphia Museum of Art (4) and

a further half-armour in the armoury of the Knights of St John at Malta, (5) an attribution of the morion to the authorship of Pompeo seems justified.

There is another aspect that deserves attention. An elaborately decorated morion such as the present example had most likely not been commissioned as a

single piece only, but as a headpiece for a half armour, or as a component of a garniture. Since this morion was a luxury good only affordable by the

highest ranking individuals of Renaissance Europe there remains a chance that future research might uncover to which garniture this headpiece once belonged

and who had the honour of wearing it.[...]

Condition

The present helmet is offered in an untouched conditition. All rivets and the plume holder are the original ones, still enclosing remainings of the lining

inside and of the leather that once formed part of the ear pieces. When we uncovered this outstanding piece in a South French private art collection it

suffered from severe active oxidation. So we undertook some careful conservational measures in order to perpetuate this important cultural object. However

we decided to maintain a substantial amount of oxidation in a passivated mode. Since the degree of cleaning and restoration has always been a matter of

discussion among scholars we would like to leave the decision about the adequate final state of preservation to the client. We offer to assist arranging

further professional cleanings if desired.

Notes

1) Accession Number 1982.2194.

2) Accession Number l 1982.2493.

3) Inventory Number 3476.

4) Accession Number 1977-167-37.

5) Laking, G. F. (1903), The Armoury of the Knights of St. John of Jerusalem, page 9, plate VI.

6) Inventory Number III. 4685.

7) Accession Number 14.25.656.

[...]